Invisible watermarks that protect an artist’s work are removable using generative AI models, according to a study by researchers from the Universities of California, Santa Barbara and Carnegie Mellon.

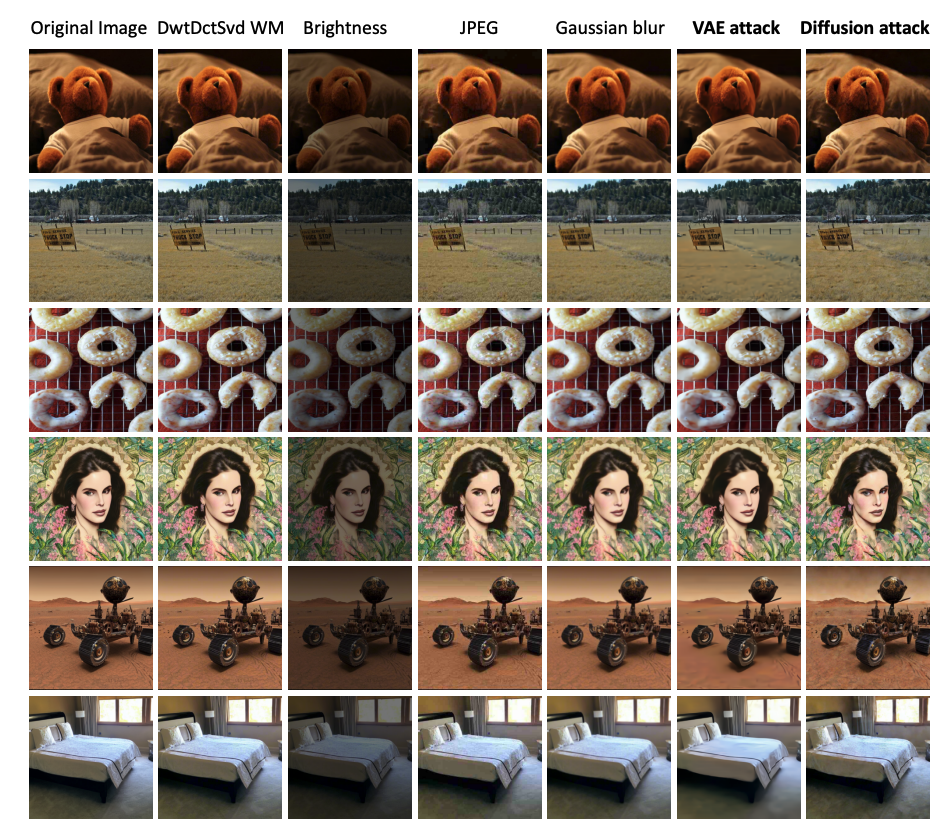

The study launched what’s known as a series of “regeneration attacks” powered by AI to test the strength of invisible watermarks in several artworks. Such attacks refer to various methods that aim to “degrade or remove invisible watermarks in images”. In the study, they included:

- Brightness or contrast adjustment: Changing the parameters of an image’s brightness or contrast to make the watermark harder to detect;

- JPEG compression: Compressing an image to lower its quality to degrade the watermark;

- Image rotation: Rotating an image can cause the watermark detector to fail to watermark an image;

- Gaussian noise: Visually distorting an image’s watermark.

AI attacks art

The researchers combined the various regenerative attack methods above, and proceeded to test them on two groups of images. The first group consisted of photos taken by humans, and the second AI-generated images.

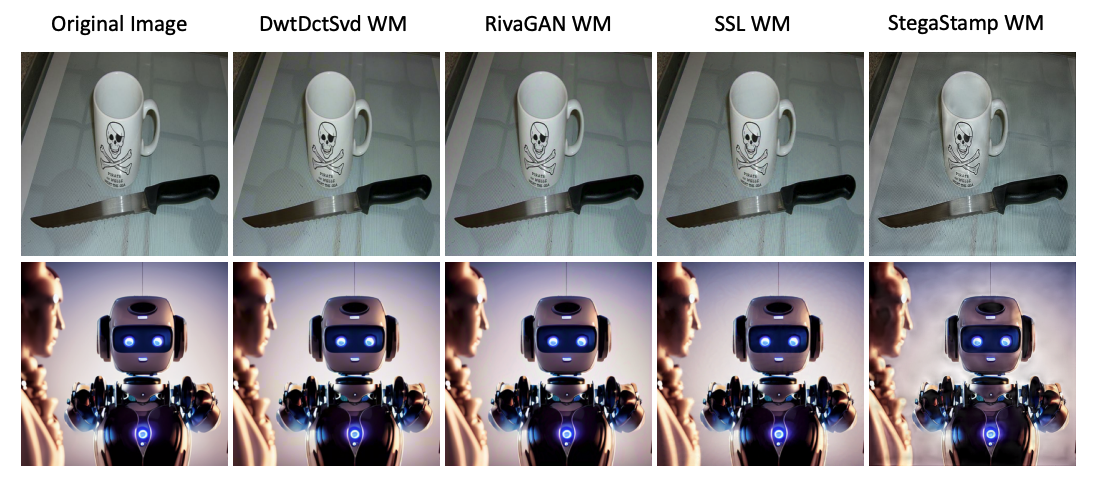

All photos in both groups were watermarked with five different publicly-available watermarking methods. They are DwtDctSvd, RivaGAN, StegaStamp, SSL watermark and Stable Signature. Among these five watermark providers, RivaGAN is thought to be the most resilient.

Unfortunately, researchers found that “all invisible watermarks are vulnerable to [regenerative attacks]”. In particular, for RivaGAN, regeneration attacks removed 93%–99% of invisible watermarks in artworks used in the study.

The full results are as follows:

- RivaGAN: 93%–99%;

- DwtDctSvd: 91–99%;

- SSL watermark: 85–97%;

- Stable Signature: 65–100%.

Interestingly, StegaStamp emerged as the watermarking method that was the most resilient against regenerative attacks, with only 1% of the watermark removed. However, authors of the paper also noted that StegaStamp “introduces the most distortion [to an image] and lowest quality��.

This suggests that there is a “trade-off” when it comes to watermarking an image. The more robust the watermarking, the lower the resultant quality of the image. So, the less likely it is to be scraped and taken by AI models.

However, researchers in the study clarified that the experiment was only conducted on invisible watermarks due to their popularity among artists. Visible watermarks – such as those used by Getty Images, for example – are potentially more robust against AI tools. But the tradeoff here is that an image’s quality could be degraded.

Artists vs. AI continues

As artists continue to tussle with scams, alleged theft, traditional protective measures like watermarking are slowly becoming less potent when it comes to fending off AI.

“Invisible watermarks are preferred [by creatives] because it preserves the image quality and it is less likely for a layperson to tamper with it. On the other hand, abusers are not laypersons. They are well aware of the watermark being added and will make a deliberate attempt to remove these watermarks,” cautioned the authors.

“Therefore, it is crucial that the injected invisible watermark is robust to evasion attacks.”

Fighting tech with tech

Depressing as it may seem, fortunately there are new tools like Glaze that claim to be able to withstand the above forms of attacks.

However, Glaze is perhaps the only tool of its kind that serves artists instead of prioritising commercial interests. The tool is developed by a team of computer scientists at the University of Chicago in collaboration with human artists. So, the lack of financial incentives is why Glaze is trusted by artists.

“Building security software is always challenging, and the problem with software [like Glaze] is that there’s always a cat-and-mouse process going on,” Professor Ben Zhao, chief scientist behind Glaze, has previously told The Chainsaw.

In an interview with us in a story about Glaze, Professor Toby Walsh, chief AI scientist at UNSW, also said: “AI companies are not interested in protecting artists – their tools depend entirely on ‘stealing’ the IP of these artists. Protecting that IP would destroy their business model.”