Move-to-earn: Are you sick and tired of walking around for free? Done with putting yourself through all the efforts of bipedal human locomotion completely unpaid?

Well fret no more — developers in the ‘move-to-earn’ (M2E) space want to fix this problem and pay you for every step you take. Whether you’re trekking to and from work or just pottering around the house while making your dinner, you could actually be earning some passive income.

Sounds a little too good to be true, right?

Unfortunately for those wanting to make a quick buck for getting those steps in, it probably is. So, to properly figure out why the M2E space should be approached with a healthy dose of caution, we need to investigate the meteoric rise of M2E and figure out whether or not pioneering projects like STEPN can survive over the long term.

The rise of move-to-earn

The M2E space was initially kicked off by a non-blockchain-based project called Sweatcoin, which launched back in 2015. Sweatcoin paid its users a really small amount of currency called a ‘sweatcoin’ every time they took 1000 steps. After users accrued large sums of these sweatcoins — often over years of daily use — they could trade them for lifestyle products on the app’s native store.

Over the years, Sweatcoin proved that businesses can simultaneously pay their users to adopt healthier lifestyles while turning a profit from partnerships, ad revenue and data collection — revenue streams that would be impossible for anonymity-focused blockchain projects to copy.

Following Sweatcoin, the M2E space stayed relatively dormant until retreating Covid-19 lockdowns ushered in a new wave of movement-starved people looking for incentives to get them moving again.

When this newfound love for incentivised fitness met blockchain technology — which made investing in these projects easier than ever before — an accidental M2E craze was born.

Following this alchemical blend of blockchain tech and Covid-driven craving for movement, in mid-March this year, an Aussie-based Web3 called STEPN brought an international spotlight to the M2E space.

As the news broke of users paying upwards of $2000 for a single pair of NFT sneakers and YouTuber Sebbyverse claiming that he earned $219 worth of STEPN’s native GST token just by walking from his house to a local restaurant to collect dinner, the M2E frenzy grew to a crescendo.

How does STEPN really work?

To actually earn money users need to mint — or purchase second-hand — a pair of STEPN’s NFT shoes. Each pair of shoes comes with a certain set of attributes that make it unique, with the rarer shoes providing the potential for higher earnings.

STEPN is a great example of a self-fulfilling prophecy. After the STEPN project won the Solana Hackathon and secured widespread promotion across the Binance exchange following a partnership agreement, the ecosystem’s native GST and GMT tokens saw a swift spike in value.

This meant the rewards being paid out to STEPN users were of much higher value, leading to an increase in people rushing to buy more expensive shoes in an attempt to access some of these increasing returns.

GST is STEPN’s utility token and it’s what users are paid rewards in. GST has an unlimited supply and is earned when users move around. This token is then used for all in-game upgrades and services such as minting new shoes and repairing or levelling up currently owned shoes.

Similarly, GMT is STEPN’s governance token and provides access to gated in-game features. For example, only users level 30 or above are eligible to swap the GMT token for a stablecoin such as USDC.

A very, very long fall from grace

To put in perspective how vastly STEPN’s utility token exploded, and subsequently plummeted, GST was listed at an initial price of just under $1 at the end of last year, and underwent a 900% gain, surging to an all-time high of $9.03 on April 28.

This rapid growth in reward price led users to pay more to mint shoes, driving reward prices higher, leading to higher mint prices… see where this is going?

Unfortunately, all of this only worked because there were increasing volumes of money coming in from all sides.

This capital influx was maintained for well over a month, due to the fact that the app successfully gamifies the user experience by integrating in-app social and market features, where users can compete with one another and trade shoes as well as other virtual goods.

Unfortunately for STEPN users, the gold rush came to an abrupt end at the beginning of May, with the GST token nosediving an eye-watering 99.6% to a tragic low of just $0.04.

The ecosystem’s GMT token suffered a similar, slightly less awful fate, dipping 80% from an all time high of $4 to a current price of $0.78.

Downward price action

This rapid downward price action emboldened critics, who have rushed to label STEPN a scam — as is the trend for criticism in the Web3 space. While the project’s tokenomics may rest on shaky ground, experts have claimed it’s not a scam. The project is legitimised by its support from partnerships with Binance and Solana Ventures, as well as substantial backing by several major venture capital firms.

That said, if we take a quick look under the hood and poke around the economics, some pretty major flaws in the project sustainability are clear. And this problem isn’t exclusive to STEPN — it’s evident across all M2E projects that rely on permanently increasing capital inflows to survive.

A quick glance at any of the charts for M2E tokens, whether it be GMT, GST or Lmypo’s native LMT, and you’ll see that they all follow a similar pattern… and no, it’s not a good one.

The troubling economics of M2E

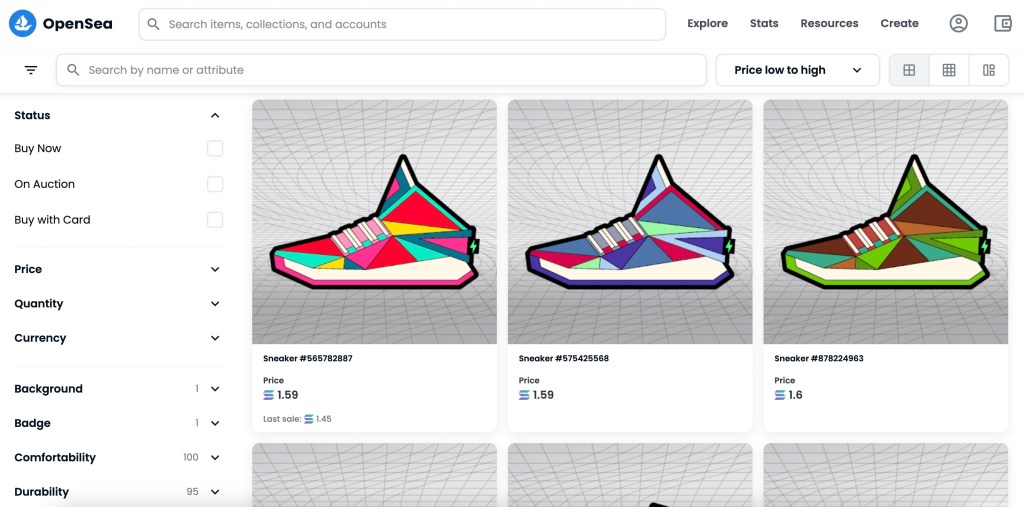

Shoes that once sold on Magic Eden for nearly $2000 a piece now sit unsold with price tags of 1.59 SOL, which at the time of writing is around $50. Both of the STEPN ecosystem’s major tokens have fallen well over 80% and trading activity on the network has slowed drastically.

The reason for this brutal collapse in price for STEPN’s NFTs can be initially traced back to the inflationary nature of rewards in the ecosystem, as GMT is effectively minted on an ongoing basis. This has many worried about the long-term viability of this project, and other move-to-earn and play-to-earn models.

At the end of the day, aside from the revenue that comes from selling the NFT shoes, there isn’t really another source of recurring income that can be used to continue paying out user rewards.

Accordingly, the STEPN team has decided to force users to upgrade their NFTs periodically (by trading in a ‘worn’ sneaker and buying a new one) or risk having them become ineffective.

The goal here is to ensure the economic sustainability of this project into the distant future, but without desirable reward amounts for users, the long-term viability of STEPN and similar move-to-earn projects appears shaky at best.

Is STEPN actually a Ponzi?

Short answer: not exactly.

Long answer: it’s complicated.

While independent market analyst Mike Fay didn’t come right out and call STEPN a Ponzi scheme, he did make it extremely clear that he thinks the general move-to-earn tokenomics model is neither scalable nor sustainable when it comes to producing revenue in the long run.

In an incisive piece for Seeking Alpha, Fay came to some pretty stark conclusions about the future of the STEPN project.

“The way this likely ends is with the last people who come into the platform essentially serving as ‘exit liquidity’ for the early adopters when the app’s in-game payment token collapses,” Fay said.

Because prices can’t go up forever, eventually someone is going to start seeing a poor return on their investment after paying thousands of dollars for a sneaker NFT. As a result, when the shoe prices grow too much, the demand for NFTs dries up and incentive drops, meaning that STEPN would have trouble attracting new users to the ecosystem. This then causes the price of GMT to drop further.

“STEPN is in a hype-driven speculative frenzy and I’m not touching any of this. Not the payout token (GST-USD), the governance token GMT or the NFTs,” Fay added.

Putting the ‘earn’ in move-to-earn

Ultimately all of the money in the STEPN ecosystem comes from a continued stream of investors. And while there is legitimate, productive value being distributed among users of the app (which vindicates it from Ponzi status), it’s simply not a sustainable model to run long-term.

Until STEPN and the other projects in the move-to-earn space can start figuring out how to properly generate sustainable and scalable systems of income while paying their users, it’s best to approach any heavy investments in move-to-earn projects with a healthy dose of caution.