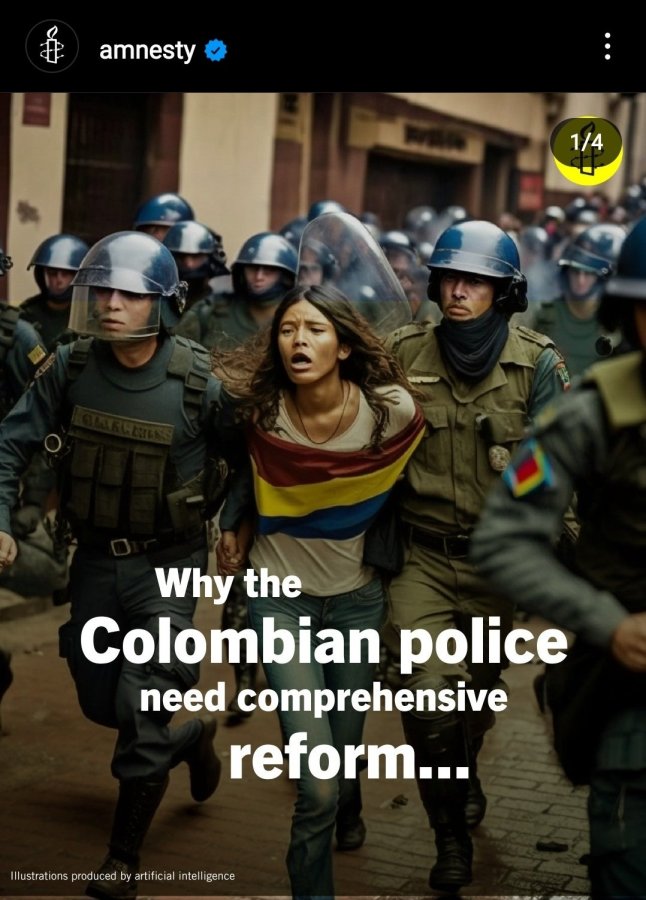

Amnesty International has faced heavy backlash for using AI art to raise awareness about protests and police brutality in Colombia.

In social media posts that have since been removed, Amnesty International Norway’s Twitter account shared a thread about the two-year anniversary of Colombia’s national strike.

The thread detailed Colombians’ struggle against police brutality, counting deaths, gender-based violence, and arrests among other human rights violations. Several tweets from the thread contained AI-generated illustrations depicting women protesters.

On the bottom left corner of the images, Amnesty disclosed that the “illustrations [were] produced by artificial intelligence.” The images were also shared to Instagram.

The tweets immediately drew backlash from users on social media. Many criticised Amnesty for undermining the voices of those who are already marginalised.

“These are real issues impacting the safety of real people in the real world… using pretend imagery only hurts those who are suffering,” wrote conservation technologist Shah Selbe, who also works with National Geographic.

AI-generated art: ethical concerns

Amnesty International told Gizmodo that its intention behind using AI art was to “preserve the anonymity of vulnerable protestors.” The organisation also claimed that it “consulted with partner organisations in Colombia” prior to using an AI art generator.

However, users online pointed out that such a move devalues the work of photojournalists who risk their lives documenting violent protests.

“Although AI images might sometimes be compelling, they can never replace the work of reporters and photographers on the frontline,” says Professor Simon Coghlan, a senior lecturer and research fellow at Melbourne University’s Centre for AI and Digital Ethics.

“The haunting photos of, say, human suffering and injustice in wars and civil rights movements are powerful partly because they are images of real people and events.” he adds.

AI art of human rights abuses: fact or fiction?

Speaking with The Chainsaw, Professor Jeannie Paterson, founding co-director of Melbourne University’s Centre for AI and Digital Ethics, says that the Amnesty International debacle provides an interesting case study on the ethics around using AI for advocacy causes.

“One of the concerns of using AI-generated images is that we start to erode the understanding of what is ‘real’ and what is imagined,” Professor Paterson says.

“AI just seems to blur this line between journalism, documentary, and imagination… [AI art] is constructed from the data that it is trained on,” she adds.

She also suggests that aside from real photos, perhaps there could be alternative mediums for organisations to better raise awareness about human rights issues, such as having an artist render images or words.

What about in Australia?

The case with Amnesty International is reminiscent of the EXHIBIT A-i – The Refugee Account virtual exhibition here in Australia.

Created by law firm Maurice Blackburn, the virtual exhibition is a documentation of life inside offshore detention centres on Nauru and Manus Island, with real statements from witnesses. Cameras and phones are banned on the islands, so lawyers behind the project turned to AI to produce images to help visualise inhumane conditions on the islands.

“To make the invisible seen and restore humanity to thousands whose trauma has been hidden from view, the statements of survivors were fed into AI technology to generate photorealistic images of what took place,” Maurice Blackburn stated on their website.

Although Amnesty International did provide full disclosure on its use of AI, it seems that in the context of journalism, things are tricky.

“Humans have a great tendency to anthromorphise if things look real. I’m just not sure that [having] a byline really has an impact that we might want to alert readers… that this is a constructed image rather than a documentary image,” Professor Jeannie Paterson adds.

However, with EXHIBIT A-i’s case, “the context makes it clearer that the images are not supposed to be real photos of human beings, even though they aim to convey aspects of the reality of the refugee experience,” says Professor Simon Coghlan.

At the time of writing, Amnesty International has yet to provide an official response to the backlash over its AI-generated art.