Blockchain database: In the aftermath of the 2017 ICO (initial coin offering) boom and bust, TradFi market participants’ primary takeaway was seemingly the mantra of “blockchain, not Bitcoin”. Since then, enterprise blockchain adoption has proliferated with a few notable failures.

Two recent examples include the Australian Stock Exchange’s abandonment of its $250 million blockchain project, as well as the recent move by global shipping giant Maersk to ditch its blockchain-enabled global trade platform. Is this an issue with blockchain or is there something else at play?

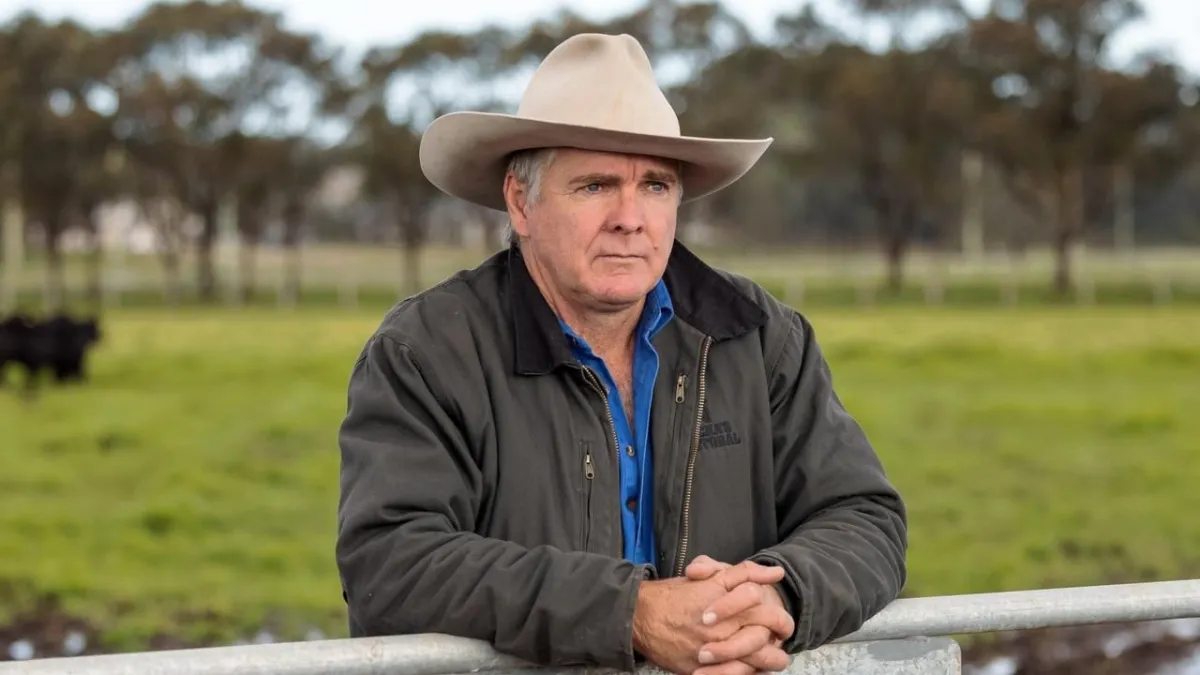

The Chainsaw reached out to Aglive, a prominent Australian blockchain business looking to shake things up in the local beef industry, to get their take. We sat down with its co-founder, Mark Toohey, to help us uncover blockchain fact from fiction.

But first, let’s talk about what went wrong with ASX and Maersk.

Where did the wheels come off with the ASX?

Last month the Australian Stock Exchange (ASX) halted its long-running and constantly-delayed blockchain project at a cost of $245 – $255 million.

The project was commissioned in 2015 and the object was to swap out the current CHESS settlement and clearing system with blockchain technology. CHESS (Clearing House Electronic Subregister System) is the computer system used by the ASX to manage the settlement of share transactions and to record shareholdings.

A blockchain-based alternative was heralded as the solution for near-instant transactions, clearing and settlement. At the time, the ASX said: “The replacement of CHESS enables the industry to meet and respond to changing local and global markets, and promote further innovation through new levels of functionality, open standards and flexible technology”.

What went wrong?

That was the plan, so what went wrong?

A report by Accenture found that despite numerous delays over seven years, the project was only 63 complete. In its detailed findings, the firm cited “poor design”, “undue complexity”, “inefficiencies”, “siloed execution”, “inconsistent quality management”, and “misaligned views of status on delivery progress, risks and issues”.

The report didn’t go so far as to say that blockchain technology was the issue, but did provide a clue that perhaps blockchain wasn’t suitable for at least part of the solution. The report noted that:

“VMware’s VMBC Ledger (the blockchain) is built to provide resiliency, immutability, and provability of data. However, CHESS use case primarily uses the ledger for resiliency which adds undue complexity to the solution e.g., the consensus contributes to the round-trip latency.”

Accenture report on the ASX blockchain CHESS replacement

In other words, it proved to be a royal mess from design to execution – but not an outright condemnation of blockchain technology at its core.

While the ASX said that it would be evaluating the underlying suitability of the technology for a future replacement, digital assets lawyer Michael Bacina was quick to comment that, “It’s important to note that the ASX project has not been cancelled due to any underlying problem with blockchain or distributed ledger technology”. Instead, he argued that it was a failure in execution since “software implementation is difficult”.

What about Maersk?

Blockchain database: Late last month, IBM and global shipping giant Maersk announced that they were abandoning shipping blockchain TradeLens by early 2023.

TradeLens was founded on the vision of digitising the global supply chain in a manner that was open and neutral. The goal was to improve global trade efficiencies by connecting supply chains on a permissioned blockchain. It was open to shipping and freight operators, and members could validate the transaction of goods as recorded on a transparent digital ledger.

In the end, it was all about efficiency and transparency. Well, that was the intent, but some five years down the track and they’re pulling the plug. According to Maersk,

“Unfortunately, while we successfully developed a viable platform, the need for full global industry collaboration has not been achieved. As a result, TradeLens has not reached the level of commercial viability necessary to continue work and meet the financial expectations as an independent business.”

Rotem Hershko, Maersk’s Head of Business Platforms said that notwithstanding, “Maersk will continue its efforts to digitise the supply chain and increase industry innovation through other solutions to reduce trade friction and promote more global trade”.

Adding further, Hershko said that, “We will leverage the work of TradeLens as a steppingstone to further push our digitisation agenda and look forward to harnessing the energy and ability of our technology talent in new ways.”

In the end, Hersko conceded that the idea to connect the global shipping economy through a blockchain had failed, “despite some early wins”. “TradeLens ultimately failed to catch on with a critical mass of its target industry”, he said.

Blockchain database: Failure

So there you have it, Maersk’s shipping blockchain efforts failed largely due to a lack of commercial uptake, with no specific mention of whether the underlying technology was to blame. Others however had a different view.

Against this backdrop, let’s turn to our discussion with Aglive’s co-founder Mark Toohey, who also happens to be a law lecturer in a MSc course on blockchain and cryptocurrency regulation. He shared some fascinating insights with The Chainsaw on how blockchain is perhaps not the silver bullet that many think it is.

Aglive using the blockchain as intended

Aglive is an Australian-based blockchain technology supply chain business that is laser focused on the agricultural sector. Using a private Ethereum-based blockchain solution, the company is on a mission to reconnect farmers with consumers using blockchain to capture and store on-farm and supply chain data. It both stores and distributes key consignment documents and certificates to help producers earn higher margins for the food and products they produce.

In conversation with The Chainsaw, Aglive’s co-founder Mark Toohey offered a first principles approach by zooming out and giving a high-level overview of his take on blockchain technology.

“It is a fact that most losses are not caused by technology [blockchain]. Instead, the root cause is the way those tools are being deployed. We must use the right technology for the right task”, he said.

“If you want to use blockchain like a database… don’t. Just use a database instead. Blockchains and databases both just store data. For most use cases, databases are more refined, efficient, and effective. But not for all cases. Blockchains do have clear advantages if you need a decentralised system that can securely handle snippets of data from a variety of sources, then blockchains will work well”.

Toohey is clearly not prone to buying into much of the blockchain and crypto hype, adding “good projects that embody social, economic, or technical benefits have unfortunately often been left withering, while the massive herd stampede chased after the latest hype-driven debacle”.

Instead he advocates for “balanced design”, using “the right technology for the right task”.

For him, the crucial advantage that blockchains have is that they are able to use disparate data from a variety of sources to form a ‘common data’. He considers blockchain technology as a “neutral tool” that allows participants to insert little bits of information relevant to the overall common purpose.

Blockchain database: Aglive

In the case of Aglive, the common goal is to create more supply chain transparency and trust in the beef industry. Toohey offered some remarkable insights on how the beef industry works and just how many data points there are to be captured.

Interestingly, every animal must have a RFID (an ear tag), a property code and cannot be moved from A to B without a requisite biosecurity permit. There are also conceivably a host of other variables that could be included in the dataset, from breed identification to sustainability.

Toohey spoke of how a combination of hardware and software could automate much of the process. He gives the example of a mobile weighing scale with a salt lick that attracts the cattle. Upon walking on top of it, it scans the ear tag (hence identifying the animal) and weighs it, providing actionable insights for the farmer and supply chain participants.

In practical terms, with the right combination of hardware and software, market participants will be able to track an animal’s movement along the entire supply chain.

Aglive is presently focused on data collection and has completed a series of pilots. At present, over 50,000 animals are being tracked on the platform, and no doubt, the results will help the business continue to expand the realm of what’s possible based on market feedback.

It’s still early days, but Toohey is bullish on the technology and its ability to offer complete transparency across complex supply chains. However he is quick to caution that prior to launching a blockchain project, it is critical to understand its inherent strengths and limitations.

“Allegations that blockchains are not fit for purpose is like complaining that a specialist off-road vehicle does not perform well on the race track. Of course it doesn’t. It never will. It is simply not designed for speed. Use it correctly and the results will be as expected.”

Blockchain database: Rounding things out

Through the examples of ASX, Maersk and Aglive it is evident that blockchain is not the silver bullet some believe it to be. In other instances, it could prove to be enormously valuable. In short, one shouldn’t try to fit a square peg into a round hole.

Even though ASX and Maersk both deliberately avoided citing the underlying technology as the issue, it is conceivable that in both cases, the technology was found wanting (aka unsuitable).

From an optics perspective, ASX and Maersk had invested seven and five years respectively into their blockchain projects and an admission that it failed due to technology choice would be more damaging from a reputation perspective, than blaming the execution or lack of commercial interest.

In fairness though, it’s also just as plausible that in both instances, it was execution and strategy that was the underlying problem. It’s hard to say without having detailed insight into the respective projects.

Irrespective, it’s clear that blockchain isn’t necessarily the answer for all supply chain businesses. That’s not conceding defeat as much as an acknowledgement of reality that embracing blockchain entails tradeoffs.

As Mark Toohey noted, “databases are good at what they do and they’ve had decades of improvement; but to shift away from that, it needs to do something special”.

And that’s really the point.