If deepfake humans irk you, science now has an explanation for that. A study by researchers in Europe published by Nature found that our brain responds more positively to human smiles we are told are real as opposed to those deepfakes generated by AI.

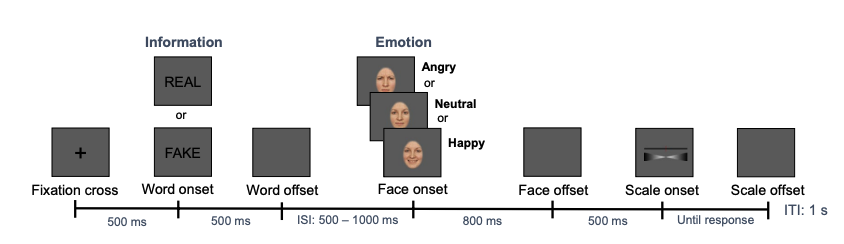

The researchers gathered 30 participants who have a mean age of 25 years old. They were given a total of 540 images of different human faces with a Caucasian appearance. The images contained three distinct expressions: angry, neutral and happy. The photos were also “cropped into an oval shape, excluding hair, ears and neck” to minimise the degree of judgement towards physical appearance.

Half of the 540 photos were labelled “REAL” and the other half were labelled “FAKE”. Participants were told that the supposedly “FAKE” images were generated by AI. But keep in mind – none of the images used in this study were AI-generated.

Deepfake humans are a no

Participants in the study were asked to evaluate the images, and respond to two prompts: whether the images were real photos or AI-generated, and if the expressions in the images were angry, neutral or happy.

The study found that images marked as “REAL” where humans are shown happy and smiling elicited “canonical emotion effects” – they stirred up more emotion among the participants, and were rated more positively overall.

On the other hand, participants generally showed a negative perception towards images marked as “FAKE”.

But both “REAL” angry faces and “FAKE” angry faces stirred up a similar level of negative emotion. This suggested that “angry deepfakes have a similarly strong impact as angry real faces”, according to the paper.

The study also recorded participants’ response times when categorising the images. They saw that when it came to categorising “REAL” happy faces and “FAKE” happy faces specifically, participants took longer than usual to distinguish between which ones they thought were real, and which ones they thought were AI deepfakes.

We are very cautious when AI is involved

“We are on guard against angry-looking agents who might harm us, whether they are real people or artificial agents. But a smile matters less when the person we are confronted with actually — or presumably — doesn’t exist,” the authors said.

“If you’re told something is fake, you’re likely to search for flaws. To spend more time interrogating something or to fixate on its negative aspects because you want to impress–to be seen as possessing the artisanal eye of the discerning critic,” explained Dr. Thao Phan, research fellow at Monash University’s node of the ARC Centre of Excellence on Automated Decision-Making and Society.

“That has more to do with performative politics of taste (which is shot through with classist and racist assumptions) than it does with raw human reactions to AI-generated images. But just because something is labelled as fake doesn’t stop us from experiencing very real emotions and attachments,” she added.

We just dislike fake art

Why was this study important? As AI-generated deepfake content floods the internet, and opportunistic actors use the technology to spread misinformation, the researchers explained that it is crucial to understand how such (mis)information influences how we think, feel and act.

“To date, the psychological and neural consequences of knowing or suspecting an image to be a deepfake remain largely unknown,” the authors stated. “When real and fake faces are otherwise indistinguishable, perception and emotional responses may crucially depend on the prior belief that what you are seeing is in fact real or fake.”

This is not the first scientific study that attempted to analyse our underlying bias towards AI-generated content.

In August, researchers from the University of British Columbia (UBC) similarly found that humans displayed a negative bias against songs and images that they were told were generated by AI (the two pieces of music in this experiment were created by AI, but participants were told one was generated by AI and the other a piece of original music).

This is because we strongly feel that creativity defines what it means to be human, and AI-generated content poses a “threat” to our humanity.