“If we are consuming for the sake of consumption, what’s the point?”

Laura Thiele, a Melbourne artist and animator, says her first reaction to OpenAI’s powerful new tool Sora, was that of “fear”.

“Art and animation as an industry copes pretty well with adaptation, but there comes a point where we are no longer artists and animators,” she adds.

While generative AI tools like Sora have been around for years, Sora’s ability to produce high-quality, photorealistic moving images combined with complex camera motion have made it the talk of tech and creative circles since its release.

“This could be the ‘holy shit’ moment of AI,” wrote The Verge editor Tom Warren.

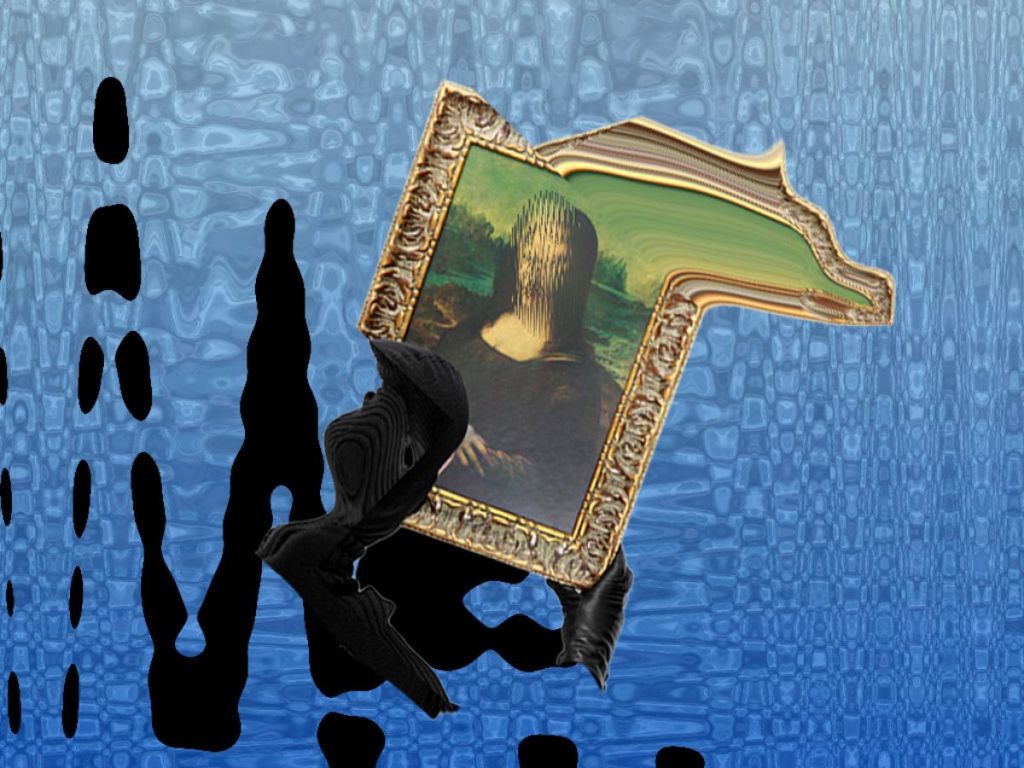

Sora has thus reignited debate on OpenAI’s values as a company, the ethics of how AI-generated art is produced – and most of all, whether ‘art’ created by AI can be considered a legitimate form of art.

Unethical, ‘closed’ OpenAI

Generative AI tools like Sora, as it stands, are unethical, Thiele tells us.

Time and time again on social media, artists come forward and speak against AI tools’ alleged art theft, but to no adequate redress. Last year, US artists collectively filed a class-action lawsuit against Midjourney for training the company’s AI model with their art without prior consent.

With Sora, more attention this time round has been on OpenAI’s silence surrounding the text-to-video tool’s training data. If Sora can faithfully reproduce a digital world like Minecraft, what exactly was it trained on?

In a preview “under conditions of strict secrecy” to MIT Technology Review for Sora, the company also would only share information if the publication “agreed to wait until after news of the model was made public to seek the opinions of outside experts.”

“Since Sora’s release, it’s been up to technologists and researchers to tinker with it and figure out exactly what is going on under the hood,” shares Dr. Luke Munn, research fellow of AI and digital cultures at the University of Queensland.

“In terms of OpenAI’s vision and their company statement, their current attitude is not adhering to that at all,” Munn notes.

“Pulp” AI

Sora’s debut also highlights our problematic relationship with art as consumers living in a content-saturated time: the slow degradation of some art forms. Specifically, how we unknowingly, passively accept whatever is served to us on a screen.

“This is a byproduct of the attention-driven economy where if something becomes small [on a screen], it becomes insignificant and drops off the field so there is no object permanence,” Dr. Munn explains.

“What you get with [AI-generated videos] is at first glance, they look very impressive and convincing. But if you zoom in to the details or replay them, the physics start to fall apart. If you’re a filmmaker who pays close attention to footage, you typically have a higher expectation of what is needed,” he says.

Case in point: TV series Fallout and Loki’s promotional posters in 2023, which were accused of being AI-generated by fans.

Melbourne-based cartoonist David Blumenstein, who is also deputy president of the Australian Cartoonists Association, tells The Chainsaw that the general attitude among Aussie animators towards AI tools is said tools are “designed to replace us, and the most cynical employers are fine with that.”

“Nobody that I’ve seen is making AI tools to help animators [or] people with animation skill; the tools are made to help businesspeople and people without animation skills to create generic ‘content’. The goal of generative AI companies is to make all that seem inevitable, so that companies get caught up in FOMO and invest in AI without thinking too hard about whether it’s actually going to help them,” Blumenstein notes.

The cartoonist, who has created comics for The Guardian, Crikey, and Australian MAD, also tells The Chainsaw he has heard of one or two people “who are being threatened with losing their job if they refuse to use AI tools as part of it.”

Rife with exploitation

“The art industry as a whole, especially animation, is already rife with exploitation. Budget cuts, frequent untreated burnout, underpaying staff, and so on [is extremely common]… AI is essentially another tool that can be used to exploit us,” explains Thiele, who worked on popular Aussie animations like ABC’s Strange Chores and Koala Man.

“You always see people [online] say: ‘Artists’ opinions don’t matter,’ – while the statement may be true to a certain extent, it is not a reality we should be comfortable with,” Thiele passionately notes.

“You as a consumer deserve to have quality content and we as artists deserve quality of life, and that comes with valuing where content comes from.”

What’s next for animation?

Blumenstein tells us that for Australia’s animation industry, the implication of the proliferation of Sora or similar tools is the loss of talent.

“… Australia continues on its current path of losing the best artists to overseas, [if it] doesn’t fund its own I.P. properly and we continue to be largely a service economy for the USA.”

But Thiele, who herself experienced being laid off due to budget cuts, remains optimistic. Creatives and animators with rich, complex stories to tell will always have a place to thrive, she tells us.

She also strongly believes that this is the time for consumers to support indie animation projects: “Explore Kickstarter and if you’re able to, put your money towards artists and projects that you like. There are still a lot of [animators] creating 2D frame-by-frame animation… you just have to find them.”

“Art is the trading of human experience and AI cannot replicate that.”